|

CHAPTER III

PRIVATE PROFITS AND PUBLIC GAIN

CRITICISM of the Gothenburg System as a whole must

necessarily be based on (1) principles and (2) actual results,

and prominently among the former one must place the assumed

elimination of all motives of private interest. Here the

first question to be asked is, Has such elimination really

taken place ?

If those who financed the companies did so without expecting

any return whatever on their money, and gave us reason for

assuming that they were actuated by philanthropy pure and

simple, one could more readily accept the theory of an entire

absence of private interest. But the 5 per cent, which is

assured to them before any question arises with respect

to actual profits is by no means a bad return from a financial

point of view, especially as no real risk is run. It is

conceivable that a very large number of persons with money

to invest would be only too glad to have the opportunity

of a ' good thing' such as this without making any pretence

that they were merely seeking to promote the welfare of

their fellow-men. Such a position becomes still more tenable

when one thinks of the enormous sums of money invested in

commercial undertakings which do not yield anything like

5 per cent. Taking the case of ordinary stock in the railways

of the United Kingdom, I find that in 1905 no less than

£56,691,000 received no interest or dividend at all;

on £16,969,000 the amount of dividend paid did not

exceed 1 per cent.; on £42,821,000 it was between

1 and 2 per cent.; on £126,692,000 it was between

2 and 3 per cent.; and on £78,934,000 it was between

3 and 4 per cent. To talk, especially, to the holders of

the £56,000,000 ordinary railway stock yielding no

return whatever about the beneficence of the shareholders

in the Gothenburg System companies who are ' content' with

5 per cent, preference dividends would be something like

a mockery. Even in the case of the highest yielding companies

in the United Kingdom stock can hardly be bought now to

yield 5 per cent., and this notwithstanding the recent heavy

decline in prices.

Certain it is, also, that such a return on capital compares

favourably with that which is obtained from investments

in other companies in Norway, at least. Writing on this

subject in 1893, Mr. Michell, then Consul-General at Christiania,

said:

' A preferential payment of 5 per cent, on the shares of

the association is an exceedingly strong inducement for

promoting the prosperity and extension of the associations.

Their 400-kronor (about £22) shares have never fallen

below par, and'when money is cheap they fetch as much as

430 kronor in the financial market.

' The right of the municipalities to buy up at par, within

a certain number of years, all the shares of an association

alone prevents the shares from being constantly at a premium.

' The best Government securities (loans) and the bonds of

the Land Mortgage Bank of Norway do not yield a higher rate

of interest than 3 to 4 per cent. Their value is at the

same time liable to be swayed by a variety of circumstances.

The financial credit of Governments, as well as that of

land mortgage banks, comes and goes, but as drink is likely

to go on for ever to an extent, at least, that cannot fail

to give its vendors a benefit of 5 per cent, on invested

capital, it is not surprising to find that all towns in

Norway have been eager, if only from that point of view,

to avail themselves of the advantages offered by the Gothenburg

System.'

The idea, therefore, of shareholders having no private interest

in the liquor business merely because they are willing to

accept ' only' 5 per cent, is really absurd. One must remember,

again, that the Gothenburg System companies have played

an important local role as distributors of the profits for

public purposes, securing in this way a position of influence

in the community that might almost be regarded as equivalent

to a substantial bonus. For a man wanting to secure a certain

position in a small community (in addition to 5 per cent,

for himself), nothing could suit his purpose better than

to become a leading member of a licensing company.

Then it is assumed that if the licensing business is only

left in the hands of Governments or municipalities there

will be a complete disappearance of any desire for financial

gain, and that the good of the community will be the sole

aim kept in view. Such an assumption is wholly inconsistent

alike with past history and present experience. The fact

is, rather, that Governments in all lands have generally

been as keen to raise revenue out of the liquor trade as

any private individual could be to secure profits for his

own pocket, and this tendency on the part of Governments

has been reproduced more or less under the various modifications

of municipal control of licenses.

Mr. Michell said on this point in regard to conditions in

Norway :

' The municipalities themselves are strongly interested,

not only in the establishment of associations for the sale

of spirits, but also in their prosperity.

' The larger the surplus at the disposal of an association,

the greater are the benefits which the town expects to reap.

Roads, parks, waterworks, railways, schools, museums, etc.,

are priceless benefits in a country relatively so poor,

and in which taxation, local or central (already very high

in towns), cannot always be resorted to for the attainment

of such objects.

'The favour with which the municipalities and the Government

itself regard the associations in question facilitates the

establishment of their dealings on a basis satisfactory

to all parties concerned—namely, the shareholders,

the municipalities, and the central Government.'

He gave one or two illustrations of how the liquor business

was, at that time, really being promoted, in spite of statements

to the contrary, and went on:

' On all the above grounds it may boldly be asserted that

the original, purely philanthropic, object of the associations

(considered collectively) has been gradually departed from,

and that the old licensed victualler, often under circumstances

of great hardship, has been replaced throughout the great

part of the country by hundreds of

holders of 5 per cent, shares, by administrators practically

and otherwise interested in the distribution of larger and

larger surpluses from the sale of spirits, and by municipalities

well content to improve and embellish their towns without

recourse to direct communal taxation for those purposes.

The Rev. Joseph M'Leod, a member of the Canadian Royal Commission

on the Liquor Traffic in Canada, wrote of the system in

his minority report:

' However unselfish the original intentions of the Gothenburg

System, there is much reason to believe that, as at present

managed, it is simply a profitable monopoly of the liquor

traffic, in which the shareholders in the companies, the

municipalities, and the central Government participate';

while in his' Conclusions/ set forth in this report, he

said on the same subject:

' The original purpose of the system has largely been lost

sight of. Intended to save the liquor traffic from the dangerous

features supposed to arise out of the greed of individual

licenses, it has degenerated into a system to encourage

and satisfy the greed of shareholders scattered all over

the country. It also appeals to the cupidity of municipal

authorities and to that large class, found in every community,

who think they see in the revenues derived from the traffic

a relief from taxation.

Then the House of Lords Committee on Licensing said of the

Gothenburg System:

' It cannot be denied that the almost universal adoption

of this system was not due simply to the desire of promoting

temperance, but also, and perhaps mainly, to the hope of

applying the large profits derived from the sale of liquors

to the reduction of local taxation.

Other authorities have been no less condemnatory, and I

am bound to say, as the result of my own investigations,

that the whole system certainly does lend itself to a good

deal of criticism from the financial standpoint. Whatever

view may be taken as to the ' elimination' of direct ' private

profit,' it must be admitted that there has been substituted

for it (assuming such elimination to have taken place) a

public gain which is really only private advantage in another

form, and is, in effect, proving an even stronger incentive

for the conduct of| the business on strictly business lines.

Instead of private individuals, whole communities are now

interested in the profits, to which they look as a means

either of keeping down the demands jnade upon them by the

rate-collector, or of securing a host of public improvements

or ' charities ' which they would otherwise have to pay

for or support out of their own pockets, if they wished

to have them at all. Assuming that the communities do not

really want to ' press' the sales, there are local expressions

of regret if those sales go down and the available profits

decrease. The ' brandy money' has become, in fact, a most

important element in municipal finance, and, although the

salaried officers of the Bolag may proclaim absolute indifference

whether the profits are £5,000 or £10,000 more

or less in a year, I doubt if a local municipality regards

the matter from quite so independent a standpoint. The whole

idea of 'disinterested management' has proved to be only

a delusion and a snare.

A significant story as to the way in which

matters have been worked is told by Dr. Gould in respect

to an incident that once occurred at Sogne Fjord, Norway.

A physician asked the local company for a contribution towards

a certain hospital in which he was interested, but the company

pleaded lack of funds. At that time it was usual to close

the spirit bars and retail liquor shops in Sogne Fjord whenever

the fishermen returned home with successful catches, so

that they should not spend their money in drink. Acting

on a suggestion made by the physician, the company withdrew

this regulation, kept the places open on the said occasions,

and increased their business to such an extent that in due

course they were able to let the doctor have the desired

subscription.

Some years ago the prohibitionist party in Norway, as the

result of persistent agitation, secured a vote of no-license

in several of the smaller towns, and the ' Samlags' were

consequently closed. Much ill-feeling was caused thereby,

but the main grievance advanced by the press was that the

communities had lost large sources of income, and must either

do without advantages previously enjoyed, or pay for them

out of their own pocket.

The number of towns in Sweden where the Gothenburg System

is now in operation is 101. In fact, there are only seven

towns in Sweden with a population of less than 1,000 each

where it has not been put in force. One is asked to assume

that these 101 towns have all been inspired by purely philanthropic

motives in what they have done. But, when one looks at matter-of-fact

details, one finds that the net profits on such philanthropy

amounted, in 1905, to 11,338,860 kronor (£629,936).

This was in addition to 440,237 kronor (£24,458) which

the Bolags had already paid on liquor duties, so that the

gain to the communities represented a total of 11,779, 097

kronor (£654,394).

It would be really childish to expect one to believe that

these very substantial pickings have not influenced the

local communities in any way. I asked a leading citizen

in Gothenburg what would be thought of the position if the

temperance societies in Sweden were suddenly to convert

all the working classes to total abstinence from brandy-drinking.

A look akin to consternation came over his face as he replied:

' I do not know what we should do without the brandy money.

We depend on it for so many things.' While, however, there

has been every inducement hitherto for the towns to work

the trade on business lines (philanthropy notwithstanding),

there has for some years past been great dissatisfaction

on the part of the country districts because they have not

participated to a larger extent in the financial benefits.

Farmers and farm labourers, they say, go to the towns for

their branvin, and not only do they take their money out

of the district, but the municipalities gain the advantage.

There is also a party which holds that the State acted unwisely

at the outset in allowing the local authorities to have

the handling of so much money. The profits should, they

argue, be used to a much greater] extent for national, in

preference to local, purposes. This argument would

probably have prevailed years ago but for the influence

of the municipalities.

The somewhat undignified quarrel that has taken place over

the profits of a business which Swedish ' philanthropy'

would have us regard as pernicious has been one of the reasons

for the passing of a new Liquor Act, to come into force,

in towns, on October 1,1907, and, in the country, on November

1, 1907. Without going into somewhat complicated details,

it may be said that under this new law the towns will be

able to keep only a substantially smaller proportion of

the Bolag profits for purely local purposes, and will be

required to send much more to Stockholm than they do at

present for distribution among the rural districts. Thus

the latter will gain at the expense of the former, though

the effect will be (as even one of the most earnest supporters

of the Bolag system admitted to me) that ' the towns will

have less inducement to try to make money out of the traffic.'

Under existing conditions, the Bolag at Gothenburg gives

seven-tenths of its profits to the town authorities, one-tenth

to the county agricultural society, and sends the remaining

two-tenths to Stockholm for division amongthe country parishes.

It is estimated that for 1906 the seven-tenths thus to be

paid into the town treasury will be £46,666, of which

£20,291 will be used for the ordinary purposes of

local government, thus presumably keeping down the demands

on the ratepayers, and £26,375 will go to local 'philanthropic

' purposes, included in this definition being schools (one

of which gets £6,000), institutes for working men,

domestic economy classes for workmen's children, meals for

poor children, Bolag reading-rooms and waiting-rooms, concerts

for working people, parks, a home for consumptives, a labour

bureau, museums, libraries, subsidies to lawyers who give

gratuitous advice to poor people, a committee for the encouragement

of sports, and so on.

But for the existence of the Bolag system, various of these

objects would, as in England, have to be met either directly

out of the rates or out of the purses of the charitable.

The individual members of the community, therefore, have

a direct pecuniary interest in regard alike to the £20,291

added to the municipal revenue and to the £26,375

devoted to local 'philanthropic ' purposes. Whether they

want to 'press' the branvin traffic or not, the fact remains

that the greater the profits the more they will collectively

and individually benefit. I fail to see, therefore, how

it can really be said that the Gothenburg System ' eliminates'

the element of ' private gain.' There is ' private gain'

to every person in the local community upon whose purse

fewer demands are made because of the branvin money being

available, and the talk about ' restrictions ' on the traffic

must be considerably discounted by the fact that any sudden

cessation of the profits would be regarded by the general

body of ratepayers and citizens in the light almost of a

financial disaster.

One resident in Gothenburg, who had watched the system for

many years, said to me, when I asked for his candid opinion

:

' Taking the movement as a whole, there is too great a leaning

towards profits. To-day there is very little philanthropy

in the affair. If they would only give up the idea of making

money out of the business, they could do a great deal more

to promote the sobriety of the people.'

A similar view seemed to be taken by a Salvation Army officer,

who, in answer to my question as to whether or not he thought

the system was doing good, replied:

' I do not think the Bolag is making much for temperance.

In one respect it places more difficulties in the way. When

the trade was in the hands of private individuals we could

go to them whenever we saw anything wrong, and make a personal

appeal to have the matter remedied. But the Bolag is a different

matter. The leading people in the place are connected with

it, and they will tell you how much good the brandy-money

is doing in the way of public improvements or in maintaining

charities. As to raising the prices of the spirits sold,

I do not think any real good is done by that. When the men

want drink they will get it, whatever the price. If the

time should come when they really cannot afford to buy branvin,

they will have methylated spirits instead, and that is much

worse for them. If, again, you keep them from the bars,

it means they will take more spirits into their own homes;

and, though this may reduce the risk of bad companionship,

it will have a bad effect on the children. Much more useful,

in my opinion, is the reduction in the alcoholic strength

of the branvin,* but no really lasting reform will be brought

about until you get down to the hearts of the people.1

* The alcoholic strength of the branvin sold by the Gothenburg

Bolag stood at 47 per cent, from 1866 to 1883. Since then

reductions have been made as follows: 1884, 46£ per

cent.; 1888, 45 per cent.; 1899, 44 per cent.; 1902,43 per

cent.; 1904, 42 per cent.; 1905, 41 per cent.; 1906, 40-2

per cent.

For still another view on the general subject I take the

following from an address delivered by the Rev. Elis Heuman,

Court Chaplain, at a temperance meeting held in Stockholm

in April, 1905:

' Who is it that causes the public-houses to be embellished

so as to become elegant and inviting in order to allure

men and women away from their less decorated and more humble

home ? Who is it that distributes public-houses all around

the church, and gives the traffic the misleading name of

the " Gothenburg System "? Is it not Society yearning

after vile profit ? And if anyone desires to substitute

a dram-shop by a temperance eating-house, Society does not

permit this to be done. Every proposal in any such direction

is made in vain. It would diminish Society's profits on

the traffic in intoxicants.1

The extreme keenness of local authorities to get these profits

into their own hands is well shown by an incident for the

truth of which I can vouch absolutely. An Englishman settled

in Sweden had the disposal (as trustee) of some hotel property

in a town of 3,000 inhabitants, and he put it up to auction.

The sale was attended by a leading member of the local municipal

body, who tried so successfully to depreciate the value

of the property that he was the only bidder, though the

bid he made was so absurdly small that it was refused. Steps

were then taken to effect a sale by private treaty, and

a widow lady agreed to purchase, if she could make sure

of a license. On the strength of a letter written by a member

of the municipal council, stating that the license would

certainly be granted, she bought the property ; but there-

upon the council repudiated the letter of the member in

question, and definitely refused the license. In the end

the lady was obliged to let the municipality take over the

place on their own terms.

This may or may not be an isolated case ; but it illustrates

the risks that are run where a local authority has a powerful

financial incentive to get control of the trade, or even

a portion of the trade, in alcoholic drinks. Nor can the

fact be denied that abuses of other kinds have been introduced

into the application of the system in Sweden, especially

in the case of small towns, where the rents of Bolag premises

have been manipulated to the advantage either of the municipality

or of private persons; where the ' companies' have consisted

of two or three individuals ; where the representatives

of particular distilleries have joined in the movement with

the idea of getting contracts ; or where profits have been

distributed among charities started in the interests less

of the poor than of the salaried officers. While it is admitted

that such practices did, unhappily, prevail at one time

(See Appendix), it is said they do not now

occur; yet, when I mentioned the subject to one gentleman

at Gothenburg, he at once pointed to a paragraph in a local

newspaper of the previous day, stating that the accounts

of two Swedish Bolags (the names of which were given) had

just been condemned by the auditing authority, and the matter

had been referred to the King. It is not a little significant,

also, that, at the end of forty years' operations, the necessity

should have arisen practically to reconstruct the system

in one of its most essential features, the distribution

of the profits, so as to check the rapacity of the towns,

and satisfy the rival claims of the State and of the country

districts.

How the profits have worked out in the case of the Gothenburg

Bolag is shown by the following table, which I take from

the official report for 1905:

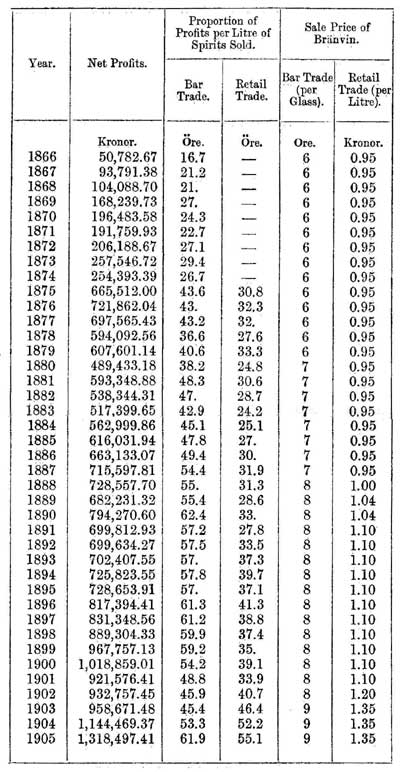

GOTHENBURG BOLAG PROFITS AND PRICES.

It will be seen from this table that the net profits of

the company, given in pounds sterling, increased from £2,821

in 1866 to £73,249 in 1905.

The reader will further observe that since 1866 the company

have made substantial advances in the prices charged for

their branvin, whether sold at the bar or in the bottle.

The reason given for these advances in price is that the

company have been inspired by a philantnropic wish to check

the consumption; and this, they say, they have done. But

it will be seen that this policy has in no way checked the

profits, which have swollen substantially with each such

advance, whether regarded from the point of view of sum

total or per litre sold. Possibly the company would have

us believe that this very substantial increase in net profits

is one of the inconveniences to which philanthropy must

be prepared to submit when it is working for the public

good—on business lines. This at least is certain, that

each increase in price throws a greater burden on the consumer,

to the advantage of classes higher in the social scale.

Whatever the precise view taken of the steady advance in

the price of branvin from time to time, one undoubted effect

thereof on habitual drinkers of the most hardened, as well

as of the poorest, type has been to cause them to leave

the more expensive branvin for special domestic or other

occasions, and take to the cheaper methylated spirits as

a steady drink. The cost of a litre of methylated spirits

in Sweden is from 35 to 40 ore the litre, as against 1 kr.

35 ore the litre for branvin. ( 100 ore = 1 krone = 1s 1-1/3d).

The patron of the former in Sweden first of all obtains

some bones, and burns them to powder, through which he filters

the methylated spirits, thus depriving them of part of their

most noxious taste. Even then the effects (I was told) are

' horribly intoxicating.'

Not so many years ago there was a remarkable and, at first,

unaccountable outbreak of drunkenness in the parish of Lindome,

near to Gothen-burg. It was known that no exceptional quantity

of branvin had been brought into the place, yet the amount

of insobriety was far in excess of that in other parishes

in the neighbourhood. Inquiries eventually showed that a

large proportion of the local artisans, carpenters by trade,

had given themselves up to the drinking of methylated spirits,

their intoxication thus being accounted for.

Opinions differ as to the extent to which the consumption

of methylated spirits has been carried in Sweden. In some

quarters I was assured it was ' enormous.' On the other

hand, the chief of police at Gothenburg told me that he

had given instructions to his force to distinguish in their

reports between drunkenness arising from methylated spirits

and drunkenness due to other beverages (a difference easily

noticeable on account of the odour of the methylated spirits),

and he had found there were not very many cases of the former.

I suspect the real truth lies between the two statements,

and that, inasmuch as the methylated spirits would be consumed,

not at public bars, but in private houses, much may be taken,

and much drunkenness caused thereby, without the matter

coming under the notice of the police in the streets. In

any case the evil has gone so far that in the new Act which

comes into force in October, 1907, the statement is made:

' With regard to the conditions of selling so-called methylated

spirits, H.M. the King has issued special regulations relating

to this traffic.' There would surely have been no need for

these special regulations unless the mischief had undergone

serious development. The resort to substitutes for branvin

has not been so great in Sweden as in Norway, the restrictions

on the sale of native spirits being less severe in the former

country than in the latter; but in considering the official

figures as to consumption of branvin the point here mentioned

must certainly not be overlooked.

|