Smithsonian - May 1994

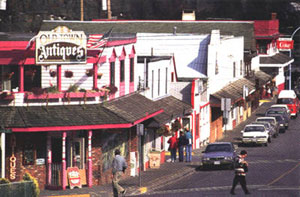

Hanging baskets of flowers adorn modest, well-kept

shops in the heart of Chemainus' Old Town, extending a festive

yet homey welcome to the 400,000 visitors who come each year

to admire its celebrated murals. |

Take a look at a town that wouldn't lie down and die

The mill closing augured ill for Chemainus. But spruced up,

with bright murals everywhere, it's turned into a Canadian

tourist haven

By Stanley Meisler |

Like mist over the nearby bay, a cold gloom hovered over the

little Vancouver Island town of Chemainus as it faced the 1980s.

The waterfront sawmill, mainstay for more than a century, was

losing millions of dollars a year. Then the government of British

Columbia agreed to subsidize a downtown revitalization program

that would spruce up the shops on Willow Street with planters,

benches and parking space. But supermarkets were sprouting in

bigger towns just a few miles down the Trans-Canada Highway. Who

would shop in tiny Chemainus, even a spruced-up Chemainus? "People

were wondering whether the town was going to die or not," says

Rodney Moore, a retired meal shop owner. The death knell seemed

sure in 1983 when the mill shut down.

Yet today, Canada's Chemainus is a thriving town, hued in sprightly

pastels, a kind of gingerbread Carmel of the North that attracts

400,000 tourists a year, most making a detour to take in 32 murals

now adorning the sides of buildings and standing walls in a festival

of color. The population has swelled to almost 4,000. It is a

spanking new magnet for young Canadians looking to put down roots

in a town with a future and for older Canadians bent on retiring

to a land of tranquillity.

Chemainus now has art galleries, sidewalk cafes, espresso bars,

craft and antique shops, gift stores and a 270-seat theater where

none stood before. The $3.5 million theater complex, serving as

the west coast campus of a drama school in Alberta, guards the

entrance to the town like an enormous, paste] orange wedding cake.

A new mill has opened, technically efficient, slimmed down, making

profits selling the highest quality knotless wood. Chemainus now

advertises itself with a copyrighted slogan, "The Little Town

That Did." The slogan may be hokey, but no one can deny that the

town, in a remarkable way, halted its slide a decade ago and transformed

itself into something new.

The word has spread. Other towns in trouble-from Queensland, Australia,

to Steubenville, Ohio-are mimicking the experience and splashing

murals on every available outdoor wall. Chemainus managed in a

decade to wean itself from dependence on a single industry. Towns

in the American Midwest and elsewhere, their economies tied to

a sputtering steel plant or a ghostlike auto assembly line, need

to wean themselves as well. Many arc embracing the Chemainus way.

Chemainus, though, has always had an advantage over most other

towns in trouble. Vancouver Island is one of the patches of scenic

paradise on Earth, forested and mountainous, with a climate so

temperate that the provincial capital, Victoria, 50 miles to the

south, almost never sees a snowfall. You can sit on a bench at

the beach at the end of Maple Street in Chemainus and watch an

occasional freighter slip past a quiet panorama of isles and inlets

beyond the bay, and you can hike back a couple of miles from town

and look on expanses of forest so vast and breathtaking that they

seem to burst out of a Frederic E. Church landscape. It is not

easy to give up on Chemainus.

Most old-timers attribute the surprising dynamism of their town

to a German immigrant, Karl Schutz, who arrived in Canada from

Heidelberg in 1951 at the age of 21. He is not admired by all.

"There are a lot of people who resent Karl because of his grandiose

ideas," says Rodney Moore. Yet even they acknowledge that he helped

turn the town around with what once seemed like a wild-eyed plan

for outdoor murals. Schutz, machinist, carpenter and businessman,

is still dreaming up schemes to promote Chemainus worldwide-and

still prompting neighbors to roll their eyes at his grandiosity.

Canadians shy away from promoting themselves, and Schutz believes

in the power of promotion.

| Canada has long been hospitable lo skilled immigrants, but

Schutz, then a journeyman machinist, could find no work in

his trade during his first weeks in his new home, a 74-cent-a-night

immigrant hostel in the city of Vancouver. But the Canadian

Pacific Railway needed crews to keep the rails in shape and

hired him for nearby Vancouver Island. He joined a crew that

worked the rails on a line that passed through Chemainus.

The crew foreman would let his men end the week's work there

so they could rush to its bank to deposit their checks. No

sooner done, Schutz would scamper down to the MacMillan Bloedel

mill on the waterfront each week and ask for a job. The heavily

accented German's weekly quest became a joke at the mill,

but after a few months the manager relented and hired Schutz

as an unskilled worker. Like so many others before and after,

Schutz found a home in Chemainus because of the mill. |

|

| |

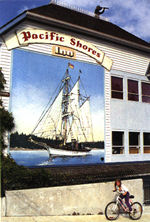

The Spirit of Chemainus painting honors

a brigantine built in the town's bay as a training ship in

1984-85 |

He started out sorting lumber at the mill but eventually wangled

a transfer to its machine shop. "And then it came to me," he says,

"this unbelievable thing about America. You can become whatever

you want. You do not have to be a machinist like in Heidelberg

because your father was a machinist." He had whiled away many

hours with carpentry as a hobby, so after five years he quit the

mill to open what became a highly successful custom woodworking

shop in Chemainus, married another German immigrant, bought a

good deal of land and retired in 1971 at the age of 40 to live

off his business profits and real estate.

|

Laundryman, grocer, bootlegger, gambler, merchant:

Hong Hing's easy credit and kind heart made him a favorite

in the town. Paul Marcano painted him outside his weathered

shop from historic photograph. |

Vacationing in Europe, Schutz and his wife came across outdoor

frescoes on the walls of monasteries of northern Moldavia in Romania.

These 15th- and 16th-century works of art, with their brightly

colored scenes from the Bible and the lives of saints, are so

magnificent that it is kind of mind-boggling to conceive of Chemainus

trying to mimic them. But Schutz does not shy away from leaps

of imagination. He did not expect Chemainus murals to rise to

the heights of religious fervor and artistic mastery that produced

the Romanian murals. But, looking on them solely as attention

grabbers, he could imagine Chemainus throwing up some kind of

murals of its own to attract tourists. When he proposed the idea

to the chamber of commerce in 1971, however, they rejected it

out of hand.

A decade later, when Chemainus received its grant to spruce up

the downtown streets, Graham Bruce, a new mayor still in his 20s,

asked Schutz to come out of retirement and prepare a plan for

future development of the town. Schutz agreed and whipped up a

plan. As Bruce, now 41, a former provincial minister of municipal

affairs and owner of the only supermarket in Chemainus, remembers

it, "We had been kicking around a whole bunch of ideas." Schutz

proposed the rejected murals as a centerpiece. "The mood was skeptical.

Then a majority began buying into the concept." Schutz finally

persuaded a town revitalization committee to go along. However,

there was still a lot of grumbling here and there.

"People did not want lo have anything to do with tourism," Schutz

says. "I told them tourism is a billion-dollar industry all over

the world. Before the war, Heidelberg existed because of it. My

divorced mother supported us by running a bed-and-breakfast."

Even alter the municipal council agreed, in 1982, lo appropriate

$10.000 to commission the first five murals, Bruce recalls, "I

remember getting buttonholed on the street and asked if I was

crazy, spending all that taxpayer money on murals when it wouldn't

make a pinch of difference."

The murals made far more than a pinch of difference. Backed by

grants from the federal government in Ottawa, the provincial government

in Victoria and local entrepreneurs, Chemainus commissioned 7

murals in 1983 and 20 more over the next nine years. Schulz and

the committee supplied the themes - almost all based on old photographs

in a 1963 book, W. H. Olsen's Water over the Wheel, a history

of Chemainus. For the most part, the walls posed artistic problems.

Artists had to avoid roof overhangs, windows, air conditioners

and doors and, in some cases, had to paint over the rectangular

indentations of concrete blocks.

The murals, the longest 120 feet, the tallest 33 feet, transformed

the look and mood of Chemainus. Most filled existing wall space,

but one mural. Native Heritage, with portraits of 19th-century

Coast Salish, the people who inhabited the east coast of Vancouver

Island before the white settlers arrived, was painted on a special

wall set up in Heritage Square, a small, new park with a fountain

and sculptures. To create Heritage Square, however, the council

had to reject a petition signed by 120 townspeople protesting

the waste of parking space. The murals do not have the sweeping

power of Diego Rivera's inarches through Mexican history. It is

hard to believe that they will ever make their way into any university's

Art 101 course. Yet, all in all, they are quiet, tasteful, pleasing,

professional works of art, and they leave a visitor, especially

on a sunlit, glorious day, with a mood of good feelings and some

insight into both the romance and harshness of a life of logging

and milling on Vancouver Island in the not very distant past.

| Even the most sophisticated tourist is affected

by their color and dignity. Genoa-born Gianna Pontecorboli,

an Italian newspaper correspondent who keeps a small but fine

collection of modern art in her New York apartment, came upon

the Chemainus murals by accident three summers ago. She and

her friend had planned to drive to the north of Vancouver

Island to take a ferry to Alaska, but traffic slowed them

down. They decided to spend the day exploring the island instead.

When they came upon Chemainus with its pastel-hued buildings

all decorated in murals, they suddenly felt like they were

entering a Mediterranean oasis in northern climes. "We decided

to lunch there and then spent hours wandering around to look

at the murals," she says. "The atmosphere of Vancouver Island

is pretty Nordic, but Chemainus was suddenly full of color.

Some of the murals were pleasant, some of them less so. But

I remember more the impression made by all of them together

with all their colors. I found it fresh." |

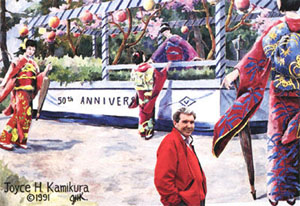

Alan Wylie's World in Motion encompasses a half-century

of historic Chemainus buildings and events. This section shows

the 50th-anniversary celebration of Victoria Lumber & Manufacturing

Company, June 1939 |

Any visitor soon chalks up favorites. My own is Waiting for

the Whistle, painted by Robert Dafford of Lafayette, Louisiana,

on the cinder block wall of Mayor Bruce's supermarket during three

weeks in 1989. Dominated by sepia and blue, this mural, the longest

in Chemainus, features scenes of workers preparing to leave their

shift at the mill in the 1940s. Since government grants cannot

be used in (Canada to commission work from foreign artists, private

donors came up with the money. "They paid us $4,000," said the

43-year-old Dafford, who was helped by his brother, Douglas. "Actually,

our minimum is $5,000, and, in terms of square footage, we did

a $10,000 mural. But we did not care about the fee. It's like

a badge of honor to muralists to have painted in Chemainus." That

badge opens the door to much new work. Portsmouth, Ohio, for example,

has commissioned Dafford to paint 40 murals on a floodwall on

the Ohio River.

| Harry Heine, an Edmonton watercolorist of seascapes, was

paid even less five years earlier. In 1984, Heine, who has

lived in the suburbs of Victoria for more than two decades,

and his son, Mark, painted a pair of marine murals in the

subtlest of soft blues and foaming whiles. The tranquillity

of the mural H.M.S. Forward, which depicts Coast Salish on

the shoreline watching the arrival of a Royal Navy gunboat

in the 1860s, sets it apart from most of the other, more-kinetic

murals. "At the beginning, tile artists virtually gave the

murals to the town," the 65-year-old Heine says. "They paid

us $3,000 for the two. But they paid all our expenses as well.

And I'm a watercolorist. I paint quite fast. As it turned

out, one of the galleries in Chemainus now sells a lot of

my paintings because of the murals. So I've made money on

tile deal. It paid off." |

Japanese float, winner in parade marking the golden

jubilee of Chemainus' mill, is commemorated in this mural.

Karl Schutz, who devised the town's revitalization strategy,

strolls by, savoring the project's success. |

Armed with old photographs, the muralists set down the history

of Chemainus. Sometimes, though, they indulged their poetic license.

Painting Company Store from a circa 1917 photograph of the store

at the old mill, Dan Sawatzky, who now lives in Chemainus, slipped

an anachronistic product on one of the shelves-''Schutz Brand,

A-l"-in honor of the man who inspired the murals. The historic

allusions, of course, make them more meaningful lo old-timers

in Chemainus than to tourists. Crystal Holman passed the corner

of Victoria and Willow streets one Saturday morning and found

SMITHSONIAN photographer John Livzey taking a shot of Lenora Mines

at Mt. Sicker. "You're taking a picture of my father-in-law's

work site," she told Livzey. More than 80 years ago Albert Holman

had helped dig the railroad tunnel leading to the mines.

The modern history of Chemainus, which lakes its name from the

language of the Coast Salish, was determined mainly by the great

forests of Vancouver Island. The Hudson's Bay Company, which once

owned the island, did not sell a tract in the area to a white

settler until 1858. Early settlers soon realized that their wealth

lay in wood. Lumber could be floated easily into Chemainus Bay

(or Horseshoe Bay, as it was called then). A stream emptied over

a 50-foot drop into the bay at the future town site, cascading

with enough power to run a waterwheel. The first mill, powered

by water, opened in 1862. No other sawmill operation on Canada's

Pacific Coast can trace its history that far back.

Chemainus was never much of a town - at least until recently.

By 1883, only the mill, two houses, six shacks and a company store

doubling as the post office stood there. Until 1886, when the

railroad came, the townspeople reached the outside world only

by steamer or boat. Although the guest register of the Horseshoe

Bay Inn reveals that two prominent personages-American millionaires

John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie-visited Chemainus within

ten days of each other in 1900, presumably to sell some of their

timberland to the mill, the town was hardly a haven for tourists.

The total population was only 600 in 1921, about half of it Japanese,

Chinese and Coast Salish laborers. There were no electric streetlights

until 1927 and few street signs until 1951. Chemainus was best

known, aside from the mill, for the Sawdust Shifters, its indefatigable

baseball team.

The Rev. Mervyn Skey, resting in pew at United Church,

says retirees lead the procession of new residents.

Co-owner of a Native artisans' studio, Herb Rice is

ex-president of the Chemainus Arts and Business Council.

|

The mill and the murals-a dynamic

duo

The fortunes of the town always depended on the inconstant

fortunes of its mills. The present mill is the fifth to stand

by the bay. Almost half of British Columbia is covered by

forests of hemlock, spruce, pine, cedar and fir, and forest

products still account for more than half the province's exports.

Chemainus has always kept in step with the main business of

the province. That is true even in the new era of the murals.

Officials of the mill, owned by MacMillan Bloedel, behemoth

of Canada's forestry and paper industry, sometimes feel annoyed

and frustrated by exaggerations in many accounts of the miracle

of the murals. The mill owners are usually painted as villains.

By closing the mill, according to these stories, MacMillan

Bloedel brought the town to its knees; muralists then galloped

to the rescue like red-coated troopers of the Royal Canadian

Mounted Police. News and television features usually play

down and even sometimes ignore the fact that a new mill opened

two years after the old mill closed. Nor do tourists understand

this. Only 900 of the almost 400,000 visitors last year took

one of the mill's twice-weekly tours. "It's nice to get a

chance to tell our side of the story," says tall, bearded,

ex-logger Al Dewar, the mill's personnel supervisor.

The mill, according to Dewar, lost a total of $17.5 million

from 1979 through 1981. MacMillan Bloedel had no choice but

to close it. "The old sawmill," says Dewar, "used to be a

spaghetti factory. We just cut wood into two-by-fours whether

they had knots or not." With the help of laser beams, trimmers

in the new sawmill search for and cut the clearest slabs of

wood out of hemlock and fir timber. The new mill specializes

in producing knotless woods, cut to sizes used in Japanese

construction. "We identified a niche in the market and went

after it," says Dewar. A number of jobs have been lost in

the niche, but the new sawmill is profitable, earning $25

million last year, according to Dewar.

Clear-eyed observers in Chemainus, Schutz among them, do not

underestimate the mill's continued importance. "This town

would lose much of its infrastructure if it closed," says

the Rev. Mervyn Skey, minister of the United (church. The

revitalization surely depended on both mill and murals. |

By diversifying its economy, Chemainus look a vital step that

other British Columbia forestry towns may be forced to take sometime

soon. Western Canada's forests are so abundant and profits from

wood and paper so important that for years few (Canadians fretted

over the cutting down of trees. This attitude has changed. Many

British (Columbians are upset over the steady loss of old growth.

Critics have decried British Columbia as the "Brazil of the North"

for denuding its rain forest, much like Brazilians are destroying

the Amazon's, and Canadians resent losing forests as wondrous

as cathedrals just to supply lumber to Japanese developers.

Delving into history has forced Chemainus to face embarrassments

of its past. As one resident puts it, the town can be "a little

redneck" and not always tolerant of minorities in its midst. The

largest minority before World War II were Japanese millworkers

and fishermen and their families. The tiny Chemainus Museum displays

a photograph of an Easter egg hunt in the 1930s for the children

of workers of the Victoria Lumber &: Manufacturing Company, as

the mill was known then, Perhaps a quarter of the children are

Japanese. Life was not easy for this minority. "We were accepted

but we weren't accepted," says 78-year-old Bill Isoki of Toronto,

a retired accountant born in Chemainus.

Japanese mill-workers were paid less than white workers; their

fishermen had a harder time getting licenses than other fishermen.

After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, Canada followed the lead of the

United States and put all Japanese-Canadians on the west coast

into internment camps. To heighten the humiliation, a gang of

toughs marched to the city cemetery on the outskirts of town and

ripped out Japanese gravestones. (Children continued to play on

some of these gravestones outside the cemetery fence for a half-century.

| Japanese and Japanese-Canadian tourists come

often, drawn both by the murals and by a need to search for

traces of the town's Japanese past. A few years ago, some

complained to town officials that the murals, supposedly telling

the history of Chemainus, left out their past. In 1991, an

embarrassed Chemainus commissioned two murals honoring that

heritage. Stanley Taniwa of Manitoba, forced out of Chemainus

as a baby and sent with his family to an internment camp,

returned to paint The Lone Scout, a portrait of Edward Shige

Yoshida, who founded Canada's first Japanese-Canadian Boy

Scout troop in Chemainus in 1929. The second mural, The Winning

Float, painted by another Japanese-Canadian artist, Joyce

Kamikura of British Columbia, celebrated a Japanese float

that won first prize in the 1939 parade honoring the 50th

anniversary of the mill. |

Daisy Bonde (left) ran the telephone exchange from

her home, 1908-15; there were only 30 subscribers. |

Most tourists do not see a third tribute. A group of Japanese-Canadians,

including Isoki, set down a small slab in the cemetery in 1991

with a handful of damaged gravestones beside it. A plaque explains

in understated tones: ". . . there was a desecration in this cemetery.

All Japanese gravestones were removed by person(s) unknown. .

. . of late some . . . have been found. These have been incorporated

into this monument which is dedicated to the memory of the Canadians,

and others, of Japanese origin who were buried in this place."

There are 30 family names on the monument.

A traditional consecration was called for

The new Chemainus has also been forced to face its Indian past.

Herb Rice and a partner joined the revitalization a few years

ago by opening up Images of the Circle, a Native crafts studio.

Rice, a 40-year-old woodcarver and former actor, is Coast Salish.

He came to town with a grievance. The mural Native Heritage featured

portraits of his 19th-century ancestors, including his own great-grandmother.

Muralist Paul Ygartua of Vancouver had drawn the likenesses from

old photographs in Olsen's history. But the portraits seemed to

give the ancestors new life, making their descendants uneasy,

and so needed to be consecrated in a traditional way to allow

the ancestors to feel peaceful in death. "My uncle told me," says

Rice, "that every time he passed the mural and saw his granduncle,

he would choke up."

A member of the Arts and Business Council, Rice soon found himself

with enough influence to do something. Speaking slowly and dramatically,

sometimes sounding ambiguous and even mysterious, Rice insists

that he has never accused the town of ill will. He managed to

persuade the council to sponsor a consecration in mid-1993 for

those portrayed in the mural. About 800 people, both Coast Salish

and whites, attended the ceremony. "It was not a potlatch, a potlatch

is for one family," says Rice. "It was a feast." After dancing

and speechmaking, the families placed four blankets on the ground,

a chair on top of the blankets, a print of the mural on the chair,

then more blankets. Traditional prayers closed this consecration.

The families gave everyone a Canadian 50-cent piece and gifts

like blankets or leather pouches as mementoes. "We felt our ancestors

had been taken care of in a traditional way," Rice says.

| Karl Schutz still busies himself

at schemes for attracting even more tourists. He is now creating

the Pacific Rim Artisan Village which, he says, will make

Chemainus and British Columbia the showpiece for the arts

and crafts of all the countries in America, Oceania and Asia

that border the Pacific Ocean. Part museum, part theater,

part school, part art shop, part theme park, the Artisan Village

will feature people from such countries as Australia, Indonesia,

Thailand, Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, Japan, the

United States and Canada, demonstrating their crafts and selling

their work. |

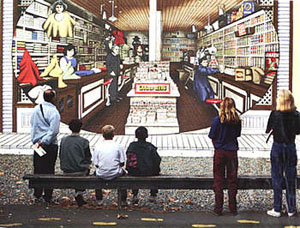

Tourists study well-stocked Company Store. Under a

then common credit system, c. 1917, buyer's coupons were sent

to the mill for reimbursement, and the total was deducted

from that employee's paycheck. |

So far the Pacific Rim Artisan Village comprises an ornate gate,

a cabin with offices, 50 acres of land, construction plans for

the first pavilion, a nonprofit foundation, a group of donors

and reams of unabashed promotion from Schutz. "Seven hundred years

ago there was a Renaissance that transformed the world," he says.

"It created millions of jobs in the crafts. It began in Florence,

Italy, with a few artists dreaming." Now, when the Artisan Village

becomes a reality, "British Columbia can achieve what Europe did

700 years ago." When his Chemainus neighbors hear statements like

that, they tend to shake their heads and mutter that Karl has

really turned grandiose this time. But a troubling thought keeps

them from ridiculing him. They remember that they dismissed Karl

Schutz as grandiose once before-when he first came up with the

crazy idea some 20 years ago of painting outdoor murals all over

town.

|